Bridging The Gap

By Richard Rosen, August, 2015

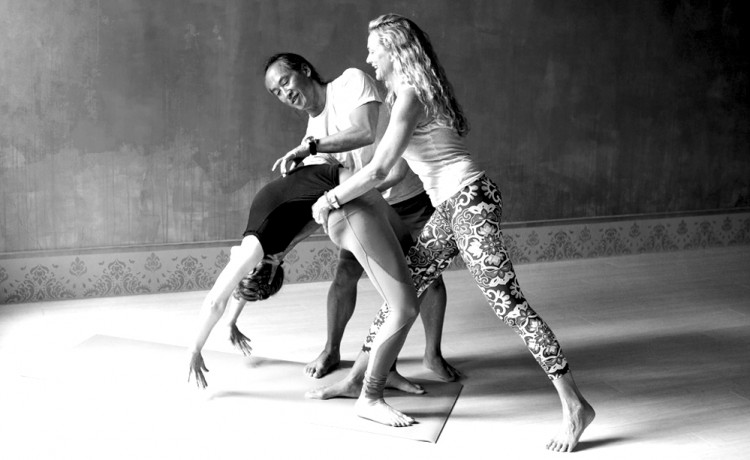

When Rodney and I were students in the three-year teacher training course at the San Francisco Iyengar Institute in the early 1980s, we learned the backbends include both “babies” and (though the name wasn’t made explicit) “adults.” Among the former are Locust (shalabha), Sea Monster (makara, usually mis-translated as something like Crocodile, Alligator, or worst of all, Dolphin), Bow (dhanu), and Bridge (setu bandha), though there was some suggestion that this one is no longer a baby but more of a tweener, like a teenager. Most of us typically enter Bridge by lifting off the floor, but in Light on Yoga (hereafter LoY) it’s is achieved by dropping back from Shoulder Stand (sarvanga), thus its formal name, setu bandha sarvanga.

Setu is a very interesting word. We usually translate it as “bridge,” but it also means “dam.” It appears in at least four of the vedic upanishads (the brhad aranyaka, chandogya, mundaka, and the maitri) as a synonym for and two-pronged symbol of the atman or essential Self (with a capital S). As a dam, the setu is said to keep our sorrow-full, mundane world separate from what’s called the brahma-world, the “happy-full” heavenly realm. But as a bridge, it provides the way for us to cross over from here to there, and “upon crossing that bridge, if one is blind, he becomes no longer blind; if he is sick, he becomes no longer sick….[and] the night appears even as the day, for that brahma-world is ever illuminated” (chandogya 8.4.2). To be more precise then, the setu is a causeway, which is a raised bank of earth between two irrigated fields that serves a dual role. On the one hand it keeps the water contained in each field, just as the Self divides our world from brahma’s; but on the other, it allows the farmer to walk between fields without getting wet, just as the Self offers safe passage between the worlds. So what do you think? From now on should we translate setu bandha as the Causeway Pose?

This message is very familiar in the yoga world: What binds us is also the means of our liberation. In all schools of yoga the key that opens the door is the answer to the $64 question: Who am I? (for those too young to have lived then or too old and absent-minded to remember, the “$64 question” is a popular catchphrase from the 1940’s, referring to a question or problem that’s especially difficult). There’s nothing else we ever need to meditate on, no mantra, no image, no breathing rhythm, but this seemingly simple question. As the Indian jnani Nisargadatta Maharaj advises us from his own experience, “Give up all questions except one: ‘Who am I?'” Paradoxically though it’s extremely important that we don’t try to answer it for ourselves, that would just lead us back to our same old self (with a small s). All we need do is hold the question in our consciousness as much as possible as we go through our days, without any expectations, without even any hope of success. When the time is ripe, when we’ve been sufficiently “baked in the fire of yoga” (as Gheranda tells his student, Canda, whose name means “glowing with passion”), the answer will make itself known.

But be prepared, it will come as a shock, not because it’s so entirely new and alien, but rather because, in fact, the answer was staring us in the face all along. As the Sufis say, It was hidden in plain sight (in this regard, read the short story by EA Poe, The Purloined Letter). We’ll stop here for now and save the rest for another newsletter.